This month, Dispatches from the Field is happy to welcome David M. Finch, a PhD candidate in the Department of Archaeology at Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador to share a story from his fieldwork adventures! Read more about David at the end of the post.

Somewhere out there is a video of me in a crater lake in Labrador doing doughnuts in a Zodiac. In reverse. It wasn’t me doing the driving, but it’s still not my preferred way to make a first impression.

I’m an archaeologist, and no, I don’t usually spend much time in craters. But in the fall of 2021, the Innu Nation asked me to go to Kamestastin Lake in northern Labrador to monitor the potential impacts of a geological base camp. About 36 million years ago, an asteroid or comet slammed into northern Labrador. Flashing forward to the present, the crater is now a lake. Geologists were studying its rim, and I and two Innu guardians (community monitors) went along – as did two astronauts! The crater is an analogue for places on the moon, so this was a way to work on their rock-busting chops before flying real missions. Most of my field camping doesn’t involve astronauts so this was a definite plus.

Archaeology usually concerns itself with the human past, but Kamestastin sits in several worlds: it’s simultaneously an ancient crater and a home to the modern Innu people. Their ancestors left traces in the region as early as 7,000 years ago and their descendants still camp on the lakeshore and hunt caribou at the river narrows. All these times are mashed together in this place and stories flow from them.

This was all new territory for me, plus I had been out of the archaeology racket for years. You know the story: bad romance, move to Yellowknife, become a consultant. It’s the northern tango. The problem was that fieldwork was my way to express myself and I had cut myself off from it. After a few years I decided that I wanted it back in my life, but in a more social way. Archaeology often involves being stuck in the laboratory (especially the forensics that I did), and historically it did its own thing without much input from non-archaeologists.

So, I put my people skills to work and got back on the land. What I study now is called community-based archaeology. A lot of it focuses on the contemporary past: near-recent events to which there may be living witnesses. These events are important to all Canadians as we try to reconcile a mess of conflicting and difficult histories. I just look at them through an archaeological lens.

It turned out that the Innu Nation was looking for partners to look at those very things. My academic supervisor at Memorial had been working with the Innu for a decade and this partnership seemed like a good fit for my interests. So this past summer, I headed to Labrador for four and a half months, to run interviews and dig square holes. It was glorious but nerve-wracking.

Archaeologists put fieldwork on a pedestal. It’s an adventure. You go to new places, do new things, prove your worth. Community-based research is like that on steroids. You throw yourself into situations and try not to worry about looking stupid. That’s how you learn. For me, the key thing is not pretending I’m the expert. The communities that I work with are full of experts, with lifetimes of experience. My job is to lend my eyes or voice when I am asked. Navigating this is how I approach reconciliation.

So, back to Kamestastin Lake: there I was, keeping an eye on the base camp and ensuring that latrines weren’t dug into archaeological sites. At the same time, Innu families from Natuashish were making their way to Kamestastin, where they have many camps and sacred sites. I was struck by how differently geologists, archaeologists, and Innu guardians travel through the landscape. Archaeologists dawdle from point to point and stare at their feet, guided by where they think people might have camped or worked. These geologists hiked long distances from outcrop to outcrop, carrying bags of rocks back to camp each night. The Innu guardians in camp expressed how much more at home they felt in the country, and for them the lake was partly a social setting. It’s the same land but seen from different perspectives.

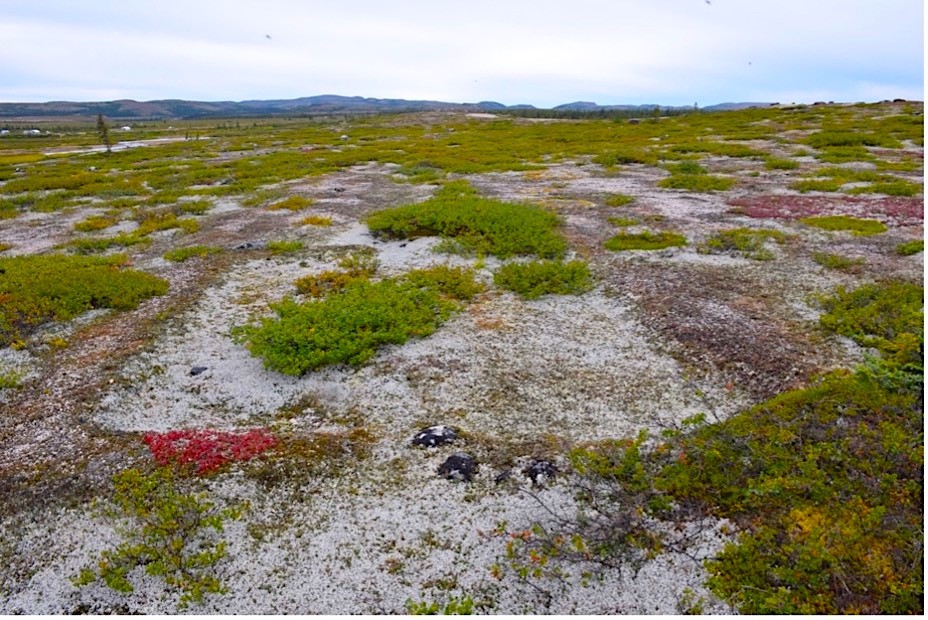

I took the opportunity to re-visit sites previously documented by the Innu and by archaeologists. Thankfully I met no bears, though there were frequent signs of their passing. The area is lichen tundra with occasional thickets of spruce and alder, and in fall the ground becomes a riot of reds, yellows, greens, and browns. The Innu gathering is timed to coincide with the arrival of caribou and the peak of berry picking.

One morning the geology crew and I got into a finicky Zodiac to head to the lake’s south shore. For almost two weeks we had been alone on the lake, but the Innu had just returned to their camp. Naturally the motor chose to act up while we had an audience. There we were, metres from shore, the motor racing… but only in reverse. That’s when the locals came out with cell phones and took video of us doing reverse doughnuts. A hundred and thirty kilometres to the nearest town and there’s still internet access. All the PhDs in the world can’t stop a Facebook post.

A day later I was on the same beach enjoying some downtime. I brought a fishing rod with me that day, and (finally!) caught an Arctic char. I reeled it in and gutted it on a plank on the shore. That’s when I realized that the cell phones were out again. The ladies on shore were delighted that I’d landed a fish, and I was told that in traditional Innu belief, the fish had allowed itself to be caught. A few days later a colleague said that she knew from Facebook that I caught that fish before I had even mentioned it.

So, everything goes in circles. Stories, boats, careers. Eventually things come around, even if backwards. The greatest thing that fieldwork ever taught me was patience. I’m glad that we found each other again.

David Finch is a northern researcher based in St. John’s, Newfoundland. Originally from Winnipeg, he has lived and worked across northern Canada. His doctoral research is on how Labrador archaeology can better reflect Innu cultural landscapes. He spends his spare time hiking, rabidly dissecting sci-fi films, and searching for the perfect bakery. Email him at dmfinch@mun.ca. https://www.mun.ca/archaeology/people/graduate-students/david-m-finch/