This week, Dispatches is excited to welcome a good friend of ours, Lauren Meads. Lauren is the Executive Director of the Burrowing Owl Conservation Society of BC – and is in the enviable position of working with some of the most charismatic (micro)fauna around. For more about Lauren and the BOCSBC, check out the bio at the end of the post.

As the Executive Director of the Burrowing Owl Conservation Society of British Columbia, I’m often asked how I wound up working in this field. I don’t have a simple answer. My path to this career — which I love — has been somewhat meandering. And honestly… birds?! I never thought in a million years that my passion for birds, specifically owls, would be such an important part of my life.

I’ve always loved animals and growing up had dreams of being a zookeeper. This led me to an undergraduate degree in Biology and then an internship working with exotic cats in the US. To further my career, I went back to school for my master’s degree in Applied Animal Behaviour and Welfare at the University of Edinburgh. My first job after finishing that program was at a zoo that focused on conservation, which drew me into the world of breeding animals for the purpose of reintroduction into the wild. My expertise in working with mammalian carnivores led me to working with raptors. And from there, I found myself working on the beginnings of the Northern Spotted Owl breeding program in BC.

Remember how I said the route was meandering? Well, after two years working with spotted owls, I decided it was time to move on to another job. During a co-op placement in my undergraduate degree, I had dabbled a bit in lab animal work and I decided to give that a try again. This was a short-lived decision, as I quickly realized that world was not for me. I longed to get back into conservation and working in the wild. Luckily, I had kept in contact with my colleagues from the Northern Spotted Owl project. When I reached out to them, they alerted me to an opportunity to work in the field with burrowing owls. That was ten years ago, in 2008. And ever since then, I have been deeply involved with burrowing owls. First volunteering, and then working in the field monitoring releases, and now overseeing the breeding and reintroduction of a native grassland species throughout British Columbia. As you can tell by the length of time I’ve been working at this job, I finally found my calling working with the Western Burrowing Owl (Athene cunicularia hypugaea).

4-week-old burrowing owls after banding. (Photo credit: Lauren Meads.)

I fell in love with burrowing owls as soon as I started working with them. I love how unusual they are among owls. While they do fly, like all owls, they also spend a lot of time on the ground hunting and roosting. They nest underground and are active during both day and night.

Unfortunately, burrowing owls are also currently threatened across North America, and endangered in Canada. Populations in Manitoba have been extirpated, while in Alberta and Saskatchewan they continue to decline. And where I work, in British Columbia, burrowing owls have been extirpated since the 1980s. While the causes of these dramatic population declines are complex, we do know that losses of burrowing mammals, such as badgers, have played a major role in the owls’ decline. Despite their name, burrowing owls don’t excavate their own burrows, but instead use those abandoned by other animals – so without animals like badgers, they have nowhere to nest. Other issues facing the owls include pesticides, increases in populations of aerial predators such as red-tailed hawks and great horned owls, road construction, and climate change. Conservation efforts are underway in all four Canadian provinces, as well as several places in the States.

In 1990, volunteers in British Columbia initiated a comprehensive re-introduction program, including three captive breeding facilities, artificial burrow networks and field monitoring research. The Burrowing Owl Conservation Society of BC (formed in 2000) produces over 100 owls each year to release in the Thompson-Nicola and South Okanagan grasslands of BC. In recent years, improved release techniques have resulted in higher adult survival and greater numbers of wild-hatched offspring with the potential to return in following years.

Preparing for release: (left to right) Leanne, Lia, and Lauren banding and assessing owls for release. (Photo credit: Mike Mackintosh.)

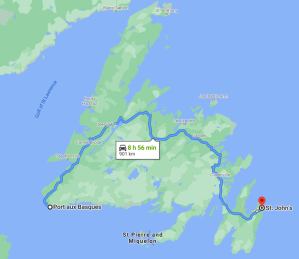

What my work looks like varies greatly depending on the season. Right now, in winter, I’m busy with the joys of writing reports and grant applications, as well as fixing the breeding facilities, installing artificial burrows in the field, and providing outreach to the public. Come spring, I and a field assistant (more than one, if funding is good!), plus some dedicated volunteers, will check each of the ~600 active burrows across our field sites. Our task is to check each one for owls returning from migration, and to ensure the burrow is in good working condition. In April, we will take the 100 owls bred in our facilities and release them into our artificial burrows. We have placed these burrows on private ranches, land owned by NGOs, Indigenous band lands, and provincial parks. This work requires a LOT of driving — sometimes up to 3-5 hours per day as we go from site to site.

After the release, we continually monitor the nesting attempts of the released owls, as well as those returning from migration, and provide supplemental food to help them raise their chicks. Along the way, we band the young born in the field. We monitor them until they all leave in September and October to head south.

Banded and ready to go: Lia, Chelsea, and Lauren getting ready to return a banded clutch of burrowing owl nestlings to the nest. (Photo credit: Dawn Brodie.)

Where exactly the owls go during the winter is still something of a mystery. We sometimes get reports of sightings of our banded owls, and we also get data from groups in the US and elsewhere in Canada that have deployed satellite tags. (We’d love to use satellite tracking tags ourselves, but they are expensive, and our organization runs on limited funds!) Based on the information we’ve received, we know that BC owls have been seen throughout the western United States, and most likely spend the winter in Mexico.

Recent years have seen an increase in the number of owls that return to BC in the spring; however, currently we still don’t have a self sustaining population. Our next step is to work on understanding the owls’ migration movements, and determine ways to increase survivability. This will involve working across Canada and internationally.

Something else I’m often asked is what the next steps are for burrowing owl conservation. Unfortunately, there’s no easy answer to this question either. While there are many organizations dedicated to conserving these unique owls, they all run on limited funds and resources. BOCSBC uses almost all of its funding breeding and releasing owls, as well as creating and maintaining the artificial burrows they use. Certainly, this is essential for the species’ recovery, but we also need to tackle the many unanswered questions about the causes of their decline before we can hope to reverse it. At the moment, there’s still so much information we’re lacking, including where the birds’ winter, issues of migratory connectivity, changes in prey availability and shifts in climate across their range.

The path that brought me to working in burrowing owl conservation was unconventional. But ten years into this career, there’s nowhere else I’d rather be!

Photo credit: Lia McKinnon.

Lauren Meads is the Executive Director of the Burrowing Owl Conservation Society of BC. She has worked with owls for over 10 years, although she still has a passion cats both big and small. She lives in the South Okanagan Valley in BC with her husband Tim and their three (small) cats. To learn more about the ongoing effort to reintroduce burrowing owls in BC, check out this video from Wild Lens. If you are interested in helping out with this project, you can contact the Burrowing Owl Conservation Society of BC at bocsbc@gmail.com or donate via Canada Helps.