In a (slightly belated) celebration of World Migratory Bird Day, Dispatches from the Field is excited to welcome this month’s guest blogger, Jenna McDermott, to share her experience watching hawk migration in Ontario. To learn more about Jenna, check out her bio at the end of the post.

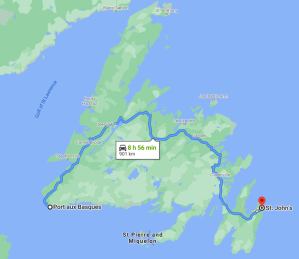

As I watch birds filter back from their wintering grounds during this spring migration, it brings on thoughts of migrations I’ve seen in the past, large and small. Migration in Newfoundland is not as grandiose or hectic as it is in places like southern Ontario, because we are a destination for most of our birds, not just a pit stop on their way elsewhere. Unlike elsewhere in North America, there aren’t really places you can go to reliably see buckets of species that don’t breed in that area. Migration in Newfoundland comes as more of a series of lovely surprises, when you realize another of your favourite species has returned for the summer.

But back in Ontario, both spring and fall migration season can be completely crazy. For a couple of years, I had the pleasure of working as the lead hawk watcher for the fall migration season at a hawk migration observatory. The observatory I worked for is part of a larger network of raptor migration observatories across North America who all funnel their data to the Hawk Migration Association of North America (HMANA). HMANA can then use these decades of data to infer trends in species populations and migration timing.

But what does being a hawk watcher mean, you ask? Basically, I stood on top of an observation tower for 8 hours every day for three months: September, October, and November. If you’ve never seen raptor migration you may think this sounds like a terribly boring job, and on some occasions it was. But most days it was an incredible testament to the power of geography, avian ecology, and the weather.

When raptors, which include hawks, falcons, accipiters, harriers, ospreys, eagles (and vultures, at hawk watches) fly long distances, they are very hesitant to cross large bodies of water. This is because they typically travel long distances by soaring high in the air on columns of warm air (thermals), and then streaming off the top in the direction they desire.Very little flapping and energy is required to do this, and when they get too low, they just catch another thermal up as if they were taking an elevator. But over water bodies, the air doesn’t heat up and create thermals in the same way, meaning birds have to flap the entire trip, which is hugely energetically expensive.

This is where the power of geography comes in. The Great Lakes are a huge barrier to migrating birds, and in fall raptor migration, the lakes funnel birds along their northern shores to locations where the birds can cross south without passing over too much water. As the migration flies by, you can expect different species to come through: for example, the Sharp-shinned Hawks and American Kestrels begin the migration season, and Golden Eagles and Red-tailed Hawks come nearer the end.

One completely unforgettable experience is the few days that the Broad-winged Hawks came through each year in mid-September. It’s such an event that birders visit from near and far and there is often a festival to bring visitors in to see the spectacle. Over a few hours, you can see thousands of these hawks gathering together and rising in slow circles up a thermal (called a “kettle”; imagine stirring a wooden spoon in a huge potful of hawks) until they reach the top and stream out right overhead.

As a hawk watcher, you often have to count them in groups of 10 as they move through incredibly quickly, while simultaneously looking at the silhouette of each one to see if a rarer species is hidden amongst the hordes. It’s a stressful, exhilarating, awe-inspiring time. On really busy days, I remember having to lay down on the hawk tower to give my neck and arms a break from looking up through my binoculars for hours on end – because looking away for even a minute could mean missing a hundred birds!

Even bigger days came at other times, such as when the Turkey Vultures were going through. Turkey Vultures often start their migration later in the morning than most species, after things warm up and the thermals are really going. During Turkey Vulture migration, you can have a quiet morning with only a couple birds passing by – and then a few hours later, you’ll suddenly see hundreds of dark spectres all floating up above the forest. Some days, nearly 10,000 vultures flew overhead…and that number is small compared to other hawk watch locations. Turkey Vultures are difficult to count because they float around so much. For example, you may think a large group is going by and count them in the hourly tally, but then some of them float back the way they came, forcing you to subtract those from ones still going past. Thank goodness for willing helping hands to sort out that mess!

Of course, on some days very few raptors passed through – just a couple or a dozen – but that made a treat out of each individual bird, and also allowed time to count the myriad other bird species in the trees below the tower or in the marsh, including the over 10,000 Blue Jays or American Crows that passed through some days. Or there would be a day of drama, such as when a Peregrine Falcon was migrating past and decided to stick around to see if it could catch a snack. Talk about a first-class seat for the show of a lifetime! And thanks to a raptor banding station at the same observatory, I was often lucky enough to get to release some pretty cool birds that had been banded and needed to be sent on their way again.

In the 6 months that I was a hawk watcher, I got frozen fingers, burnt fingers, a wind burnt face, sore neck, sore arms, blurry eyeballs, and really good at eating while simultaneously staring straight up through a pair of binoculars. But all of that is forgotten when I think back to how privileged I was to get a glimpse into each and every one of those birds’ lives as they started their long travel south for the winter.

Jenna loves to be active outside, for both work and leisure, and can often be found with a pair of binoculars ready to look at birds, nature, or far away signs that she can’t read. When she stays indoors she hangs out with a book, her partner, Darrian, and their ridiculous cat, Tonks, while ideally eating some sort of fresh baking. She lives and works in western Newfoundland.